Autistic Special Interests: Our Brain’s In-Built Coping Strategy

For the first thirteen years of my life, books were my whole world. I read everywhere, all of the time. I became absorbed in different authors’ lives and the storytelling process - I had an urge to know absolutely everything. I read everywhere, all of the time. I would even have my nose in a book walking to school - which, looking back, was probably not very safe! Books formed a core part of my identity; they provided a consistent structure to my day, and an escape when things felt too much.

I now know that books were my first proper special interest - interwoven by short-lived fascinations with dolphins and Harry Potter.

Autistic special interests are very intense, specific interests that autistic people have. They are fundamental to many of our lives. They can help us to navigate day to day life, recharge away from an overwhelming world, allow us to connect with other people and provide us with a sense of familiarity so often lacking in the chaotic world around us. Like an in-built coping strategy our brains have given to us!

Note: Not everyone likes the phrase ‘special interests’, because the word ‘special’ can be used in a derogatory way towards disabled people. Some people prefer ‘intense interests’ or ‘specific interests’, though ‘special interests’ is the most well recognised term. Additionally, there are some autistic people who don’t have special interests.

Special interests have always formed part of what autism is understood to be as a condition. Although people credit Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger as ‘discovering’ autism, Grunya Sukhareva, a Soviet child psychiatrist, actually described autistic traits years before either of them. In 1925, she identified a group of boys in her clinic in Moscow who she labelled as having ‘schizoid psychopathy’, later changing this to ‘autistic psychopathy’. She noticed that they all had “strong interests pursued exclusively”, a.k.a special interests. You can read my brief overview of the history of autism here.

Special interests can be anything at all, but here are some common ones:

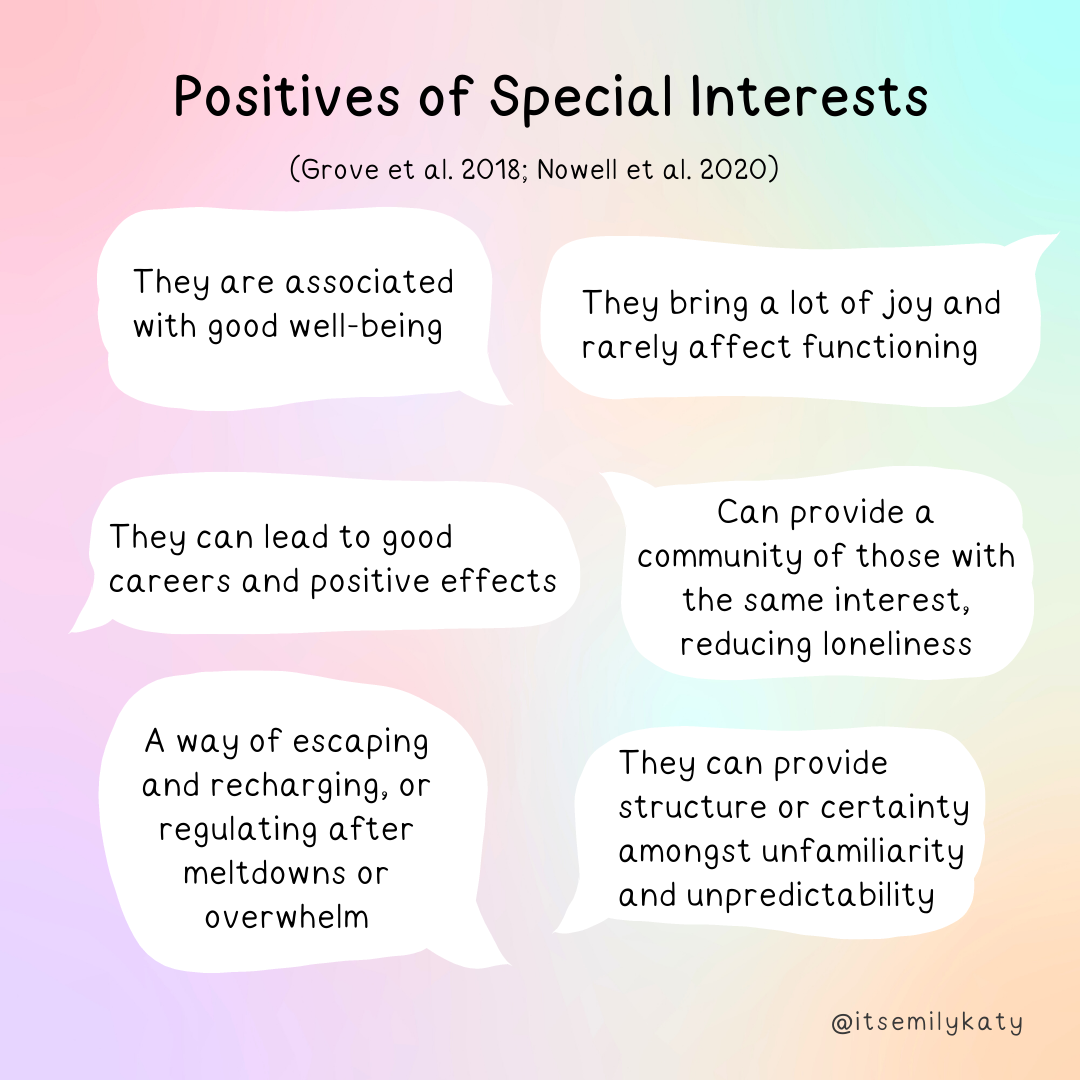

There are a lot of positives of special interests:

They are associated with good well-being in autistic people

They bring a lot of joy and rarely affect functioning

They can lead to good careers and positive effects for society

They can provide a community of those with the same interest, reducing loneliness

They are a way of escaping and recharging, or regulating after meltdowns or overwhelm

They can provide structure or certainty amongst unfamiliarity and unpredictability

(Grove et al., 2018; Nowell et al., 2021).

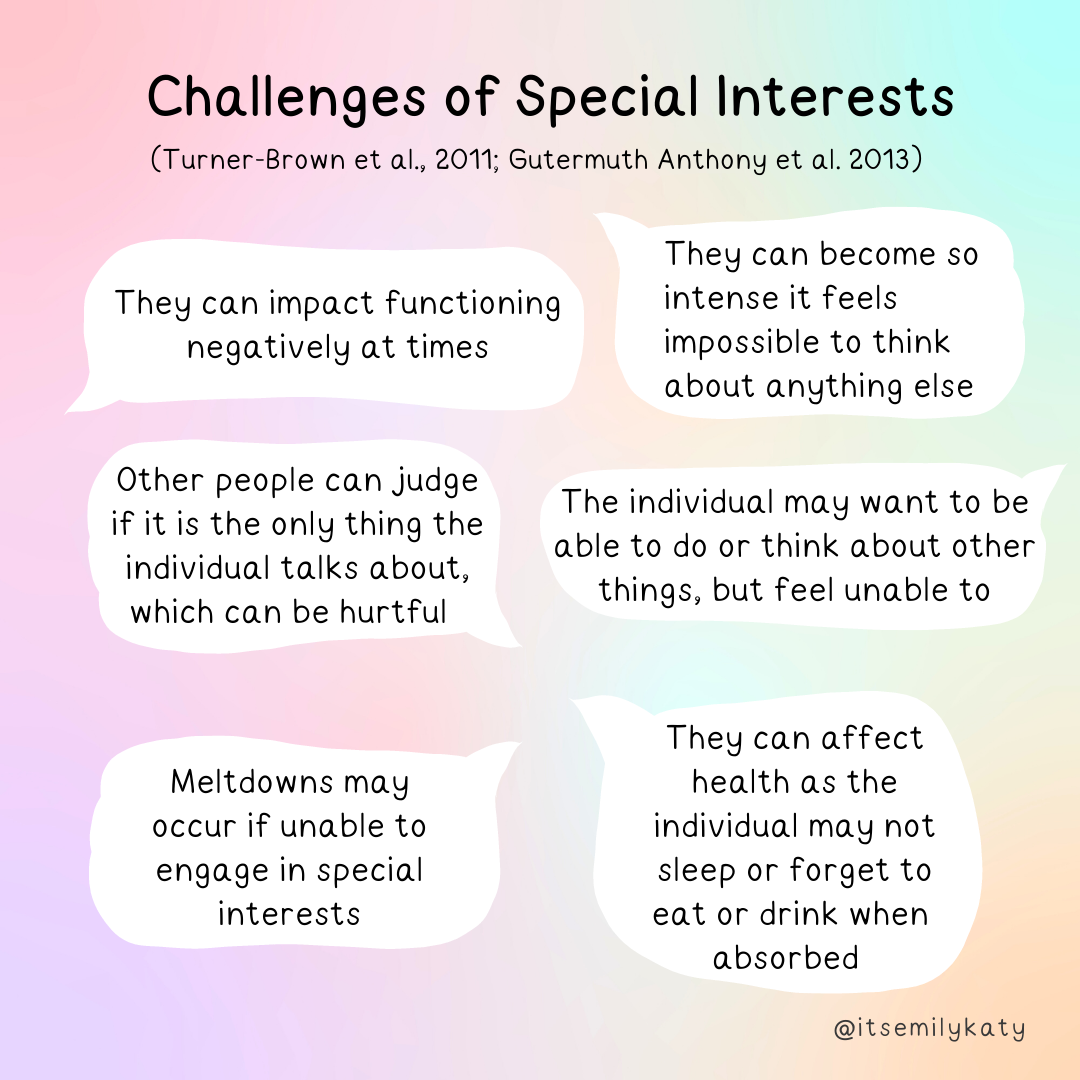

Special interests can also cause some challenges:

They can impact functioning negatively at times

They can become so intense that it feels impossible to think about anything else

Other people can make hurtful judgements if it is the only thing the individual talks about

The individual may want to be able to do or think about other things, but feel unable to

Meltdowns may occur if they are unable to engage with their interest

They can affect health as the individual may not sleep or forget to eat or drink when absorbed

(Turner-Brown et al., 2011; Anthony et al., 2013)

I absolutely love the passion and drive that special interests fuel me with, and how they can help me to recover from autistic burnout. They are so beneficial. However, there are times that they make things difficult, when I just want my brain to be able to relax and switch off but I can’t stop thinking about them!

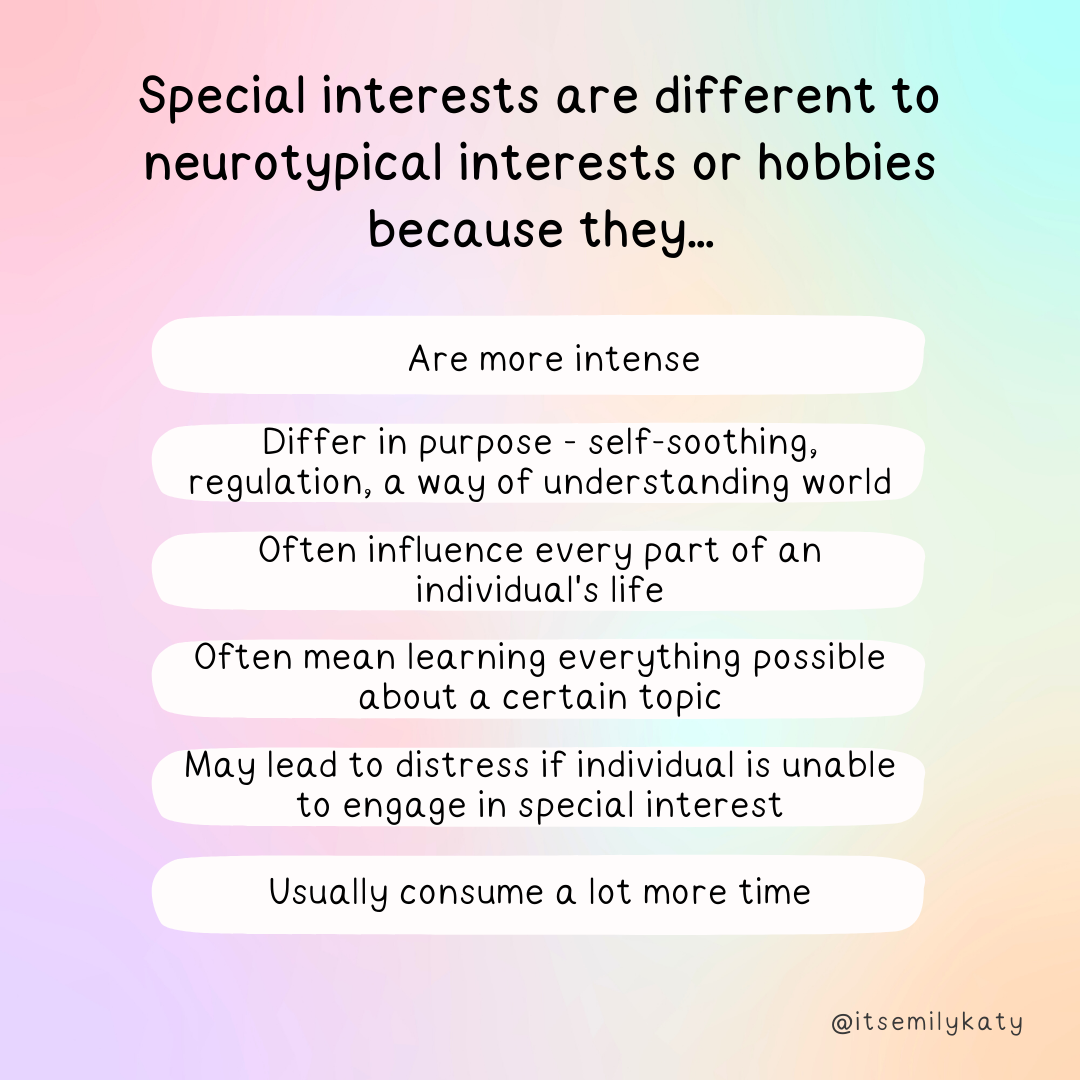

Special interests are not just interests or hobbies. They are more intense and usually consume a lot more time. They usually differ in purpose - their purpose being for self-soothing, regulation and a way of understanding the world. They often influence every part of an individual’s life and often mean learning everything possible about a certain topic. They may also lead to distress if the individual is unable to engage with their special interest.

Autistic special interests are like oxygen. They are necessary for many of us to function in this world, almost like an in-built coping strategy that our brains have created for us. We need them to survive.

If you are autistic, what is your special interest? Or what were they growing up?

References:

Anthony, L. G., Kenworthy, L., Yerys, B. E., Jankowski, K. F., James, J. D., Harms, M. B., Martin, A. & Wallace, G. L. (2015). Interests in high-functioning autism are more intense, interfering and idiosyncratic, but not more circumscribed than those in neurotypical development. Development and Psychopathology, 25(3), 643-652. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000072

Grove, R., Hoekstra, R. A., Wierda, M. & Begeer, S. (2018). Special interests and subjective wellbeing in autistic adults. Autism Research, 11(5), 766-775. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1931

Nowell, K. P., Bernardin, C. J., Brown, C. & Kanne, S. (2021). Characterisation of special interests in autism spectrum disorder: a brief review and pilot study using the special interests survey. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(8), 2711-2724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04743-6

Turner-Brown, L. M., Lam, K. S. L., Holtzclaw, T. N., Dichter, G. S. & Bodfish, J. W. (2011). Phenomenology and measurement of circumscribed interests in autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 15(4), 437-456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310386507